We perform all the time.

All. The. Time.

In performance studies, there’s extensive scholarship that explores these dimensions of everyday life. Gloria Anzaldúa, for example, writes about performances of identity-based borderlands that intersect with those that define national geographies. Judith Butler nuances how we think about gender performance. Erving Goffman examines how we present ourselves in daily life. While there are many rich areas to explore, today, I want to think with you about Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: a Kenyan writer of theory, non-fiction, drama, and novels, who pushed me to consider how we perform through language.

Ngũgĩ speaks about his relationship to Kikuyu and English: Kikuyu, his indigenous first language; English, his imposed first language. After publishing several early works in English, Ngũgĩ found himself asking a question familiar to many of us with imposed first languages: Is this really my language? For Ngũgĩ, the answer was “no.” English, he says, is not his language in the way Kikuyu is. And thus began the performance for which he is best known: Ngũgĩ began writing in Kikuyu and translating himself into English.

When I first read Ngũgĩ, I was inspired. I wanted to be like him when I grew up: “I will perform my resistance to colonialism by changing the lang—” Mid-declaration, I realized: I literally cannot write in any language other than English. Sure, I can theoretically write Hindi; but can I really write in it? No. I have never learned to write either Tamil or Malayalam. And writing in Spanish, well, how's that different than writing in English? Actually, maybe it is different bec— okay that's a post for another day.

Trying to emulate Ngũgĩ by using my non-imposed, indigenous languages felt surprisingly inauthentic. Like I was imposing on them: asking them— Hindi, Tamil, Malayalam — to become something they never have been.

There went my dreams of becoming Ngũgĩ.

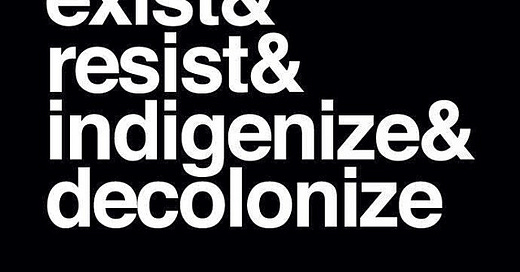

Since realizing that I couldn't perform my linguistic decolonization in the same way as Ngũgĩ, I've had to find my own ways through this terrain. Ways that feel much less radical. Solo performances — quiet, almost invisible ones — that are probably apparent only to me.

Like the choice, in my first years away from India, to not lose my accent.

Like using words, phrases, and sentence constructions that are technically English, sure, but would never be understood by speakers from elsewhere.

Like my choice of vocabulary when speaking about contentious topics like race or war or privilege. Terms that perform my solidarity with ______, and ______, and ______.

The ways in which we perform language can reveal a lot about who we are. How we see ourselves.

How we wish the world would see us.

How do you use language as resistance?